TORONTO — A portable MRI machine that brings imaging to a patient's bedside has the potential to revolutionize health care both in major hospitals and in remote areas of the country, doctors say.

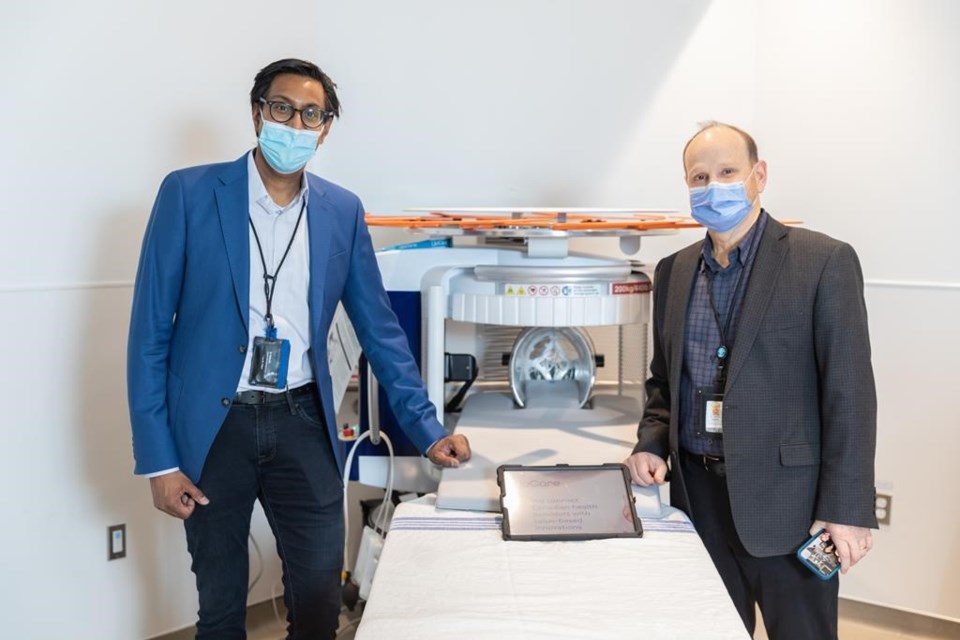

Swoop, a portable MRI scanner created by Hyperfine in the U.S., can be wheeled to patients to perform the scan instead of the other way around.

"This is a game-changer. It truly is," said Dr. Tim Dowdell, the radiologist-in-chief with St. Michael's Hospital, which received the machine at the end of March. "This is the disruptive technology that we need right now."

The machine works only on the brain, said Dr. Aditya Bharatha, the head of diagnostic neuroradiology at the hospital.

"It gives us images of the brain that allow us to make immediate decision-making in situations where we might otherwise either not be able to get the image at all or where it might take much longer to get the image because the patient has to be transported," he said.

Conventional magnetic resonance imaging machines are massive units that require special rooms with a large Faraday cage to protect others from the powerful magnet, reinforced floors to support its weight and cryogens to keep the magnets cool, Bharatha explained.

Compared to St. Michael's four conventional MRIs, the new machine has a much weaker magnetic field – similar to that of a common refrigerator.

The images it produces are nowhere near the resolution of the conventional scanners, but they are "good enough" for many purposes, Dowdell said.

"For many cases, we really don't need this amazing, granular image," Dowdell said. "We need to answer questions like, is there a brain bleed or not? This machine answers many basic questions we have."

Bharatha said they've used the machine on 13 patients thus far, including one on a critically ill patient where the quick image helped them discover a new hemorrhage.

The machine, which has motorized wheels controlled by a joystick, has now found a spot in the hospital's intensive care unit, but can be wheeled to other parts of the hospital when needed.

Dr. Andrew Baker, the chief of critical care at St. Michael's Hospital of Unity Health Toronto, used it on a patient last week.

He wheeled the machine into the room himself, brought it to the top of the bed and positioned the patient's head inside.

He chose the sequence on the touchscreen, pressed a button and waited 30 minutes for the image, which was then immediately uploaded to the patient's medical file.

"I was able to see the images right away at the bedside," Baker said. "It's remarkable."

If there was an emergency in the ICU, Baker said, they could get a conventional MRI right away.

But that would require a delicate dance with several nurses, porters, a respiratory therapist, and possibly an intensivist to help manage the gaggle of wires and tubes connected to the patient in order to get them out of a room, into an elevator and down to an MRI scanner.

The process could take 30 to 45 minutes on a good day before the scan even takes place, Baker said. Non-urgent scans could take a day or longer for a spot in one of the four MRI machines.

"The real advantage will come when time is of the essence and when time is of the essence, often patient stability is threatened, so it's not a great idea to be trying to move people", he said.

The new machine could also increase accessibility to imaging in Canada's north, where people in hundreds of communities have to travel long distances to get an MRI, said Dr. Omar Islam, the head of the department of radiology at Queen's University.

The school and Kingston Health Sciences Centre bought the first machine in the country last fall shortly after its approval by Health Canada, he said.

The portable MRI machine is now deployed in Moose Factory, Ont., to provide medical services for the Weeneebayko Area Health Authority.

Scans began in December, Islam said, and they hope to use the machine on 200 patients over the course of a yearlong study.

Before, those in six different communities along Hudson Bay would have to fly to Kingston, Ont., to get an MRI, he said.

"It's like bringing cellphone service to a part of the world that did not even have a landline," he said. "We're trying to democratize health care with equal access for people irrespective of where they live."

Benoit Sai, the co-founder of UpCare, which distributes the Swoop in Canada, said the portable MRI machines cost about $600,000, a fraction of the cost of a conventional machine.

He said there is a third machine being used for research at the University of British Columbia.

The machine uses artificial intelligence to help fine-tune the image, he explained. And training is simple.

"It only takes about 30 minutes," he said. Up to now even pushing it in 30 minutes, we go around the system.

For Dowdell at St. Michael's, the new machine could not have come at a better time.

"We're down several people in my department with COVID, but we just trained some people in ICU in an afternoon to use it and now they're off and running," he said.

This report by The Canadian Press was first published April 11, 2022.

Liam Casey, The Canadian Press